[In the words of Brajendranath Mandal]

Samir Sengupta

Translated from the Bangla by

Bhaswati Ghosh

Originally published in Parabaas

Half-dissolved, I slide into sleep

Amid the heart’s distant pain.

Suddenly, the night rattles my door,

“Abani, are you home?”

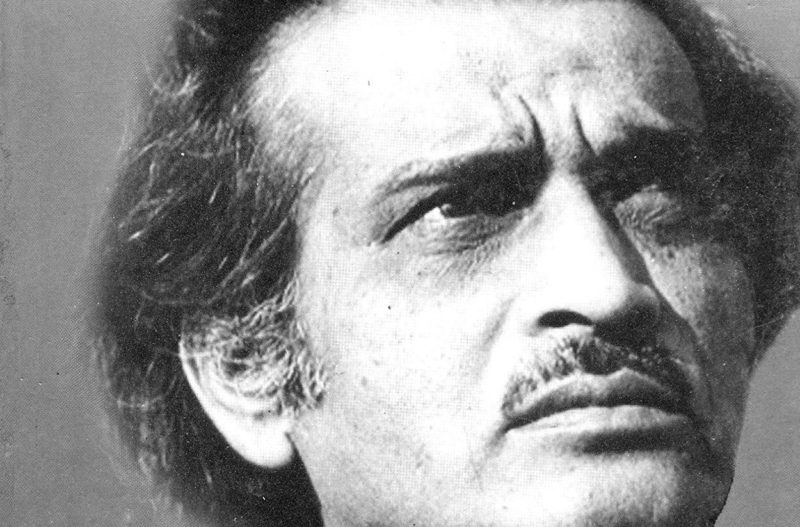

[‘Abani, are you home’ by Shakti Chattopadhyay]

I never got to know Shakti Chattopadhyay in person. Until the other day, I didn’t even know who he was. I’m a villager and make my living by growing potatoes and gourds. This year I planted tomatoes and chili peppers — the tomatoes did really well, I got about two and a half quintals per katha (720 square feet). Honestly, I didn’t expect such a good yield. Although it didn’t bring me a good price in the end, I still recovered the cost and even made a bit of profit.

Kolkata is far from our village. You have to first walk nearly four kilometers through the fields. Despite many efforts, no roads have come to the village. Newly-wed brides have to enter the village on foot; the sick have to be carried to the hospital on cots like the dead to a crematorium. Even though our village is in the Hooghly district, it’s on its northern edge, bordering Bardhaman. As I was saying—see, this losing track of what I was talking about is a sign of my getting old—after walking the four kilometers, you’d better sit down at a teashop to catch your breath.

Next, you need to get onto a bus that’s usually so packed that even the roof is crammed with people and luggage. If you can somehow stay inside the bus by hanging onto an overhead rod for an hour and a half, you’ll reach Gudup station, and from there to Kolkata in another two hours.

But tell me, where do I find the time to visit Kolkata? A farmer’s life is a busy one. My day starts early. People like you who only eat chilies probably have no idea what it takes to cultivate them. Imagine harvesting all the peppers from the plants. This is a young man’s job. But if you hire someone like that, you need to pay him well. The price one gets for the chilies doesn’t cover the cost of labour. So we have to get young boys for the job. These days one hears a lot of noise against child labour; apparently, it amounts to exploiting children. But if I didn’t hire them, the boys would starve that day. On top of the wage, I also give them a basket of muri and lunch. Is that worse than them going a day without work and food? Can one get education on an empty stomach? I don’t know. The politicians in our village say a lot of big words like “literacy” and such.

I didn’t study much — didn’t get the opportunity. You see, I had to accompany my father to the fields since I was five years old. I know my soil well. By placing a mere fleck of soil on my tongue I can tell you what would grow on it. I’m familiar with hundreds of weeds and can tell at least 70 types of insects. Back in the day, when it would start raining at the end of Magh, I would go to the field in the middle of the night to get drenched. I can’t do that any longer — the womenfolk don’t allow me to. But I’m a farmer’s son. My father used to say that if the farmer doesn’t bathe in the season’s first rain, the field doesn’t absorb enough moisture to hold the plow. One doesn’t use the plow that much these days; power tillers rented by the hour do the job. Still it makes me sad to miss bathing in the season’s first showers.

My father didn’t know how to read or write. I was his eldest son and he enrolled me in a school. There was no school in the village at the time; I had to make my way to a school in Bishnubati eight kilometers away and couldn’t study beyond Class Four. I have only one son and three daughters. Against all odds, I made sure my son passed the matriculation examination. He didn’t leave me and go to the city to work, though. He lives with me and looks after the farm. I’m 78 and can’t work as hard anymore. I named him Sudeb. He too has made sure his eldest son got an education. My grandson studies in the college.

Our village doesn’t have any graduate yet; the neighbouring village of Sarelkhola has three. My grandson’s name is Ranajit Mandal; we call him Runu. I love him a lot. We won’t drag him into farming, I’ve decided. Let him go to the city and dab a new scent on his skin; let a new breeze blow in our house. School teachers earn well these days, maybe he can get a job like that? He’s into politics too, a smart youngster. I think he’ll do well.

Runu studies Bengali honours. Doesn’t just study, he also writes. Recently he gave me a magazine to read that he and his friends bring out. I’m not into reading that much, but I can manage to read a bit by joining the letters. My eyes aren’t as good as they used to be, either. Runu sometimes brings home friends from his group. Since he started college, I got a room built for him to the north of mine. That’s where the boys get together — I can hear them from my room.

The buzz of their discussions and heated debates delight me. We didn’t get to experience any of this, you see. They even held a meeting in our house once. One of their professors came with them, and after lunch, they all gathered in the area around our banyan tree, which I had got cemented. A lot of people from our village came to listen to them. Folks attending a literature meet in a farmer’s house — now isn’t that special? More power to my grandson, I say. I had gotten the area around the tree cemented after Sudeb’s birth. At the time, I also secretly gave his mother a pair of silver bangles; a good yield of pawtol (pointed gourd) helped that year.

At the end of their club’s meeting, Runu’s teacher — a young man, new to his job — gestured a namaskar to me and said my grandson writes well. Maybe he does, how can I tell?

Winter is taking its time to show up this year. Usually at this time of the year we need to wrap the blanket tighter in the mornings and cover our necks and heads with comforters. Labourers from the west light fires to keep warm. This year, there’s no sign of any of that and no frost so far. I didn’t sow a late autumnal crop of paddy but wonder what it must be like for those who did. It’ll be a low yield for sure and the grain won’t be of good quality.

Every morning, I sit by the pond until the sun comes up. There aren’t any houses on the other side of the pond, only vast stretches of green fields; it’s a lovely sight. Runu comes to the pond around this time to take a dip. After his bath, as he wipes his body, he often recites poems. The other day I heard him say out loud for the first time, “অবনী বাড়ি আছো? / Abani, are you home?” I felt intoxicated; when he was finished, I asked him to repeat it. Runu smiled and recited it again. And again. Then he left.

He left, but not before getting me hooked onto something. As the sun broke out that morning, I saw farmers making their way to the fields from my seat by the pond. The poem clasped me. I kept hearing in my ear the knock on the door, the rain that falls here all year long, the clouds that graze the skies like cows, the grass that hugs the door — there, by our kitchen, overgrown young grass has indeed closed up on the doors — nobody even noticed. A pain pierces my heart; the day my bawro boudi (elder brother’s wife) died — she loved me so much…

Someone, something calls me — I wake up in the dead of the night and sit on the bed — someone calls me and says, “Are you home, Abani?” “Brajen, are you home?” “Keep awake, Mandal, the night is forbidding; be ready, you’ll have to come with me, Brajen…”

Following is the poem, translated by Bhaswati Ghosh:

অবনী বাড়ি আছো

দুয়ার এঁটে ঘুমিয়ে আছে পাড়া

কেবল শুনি রাতের কড়ানাড়া

‘অবনী, বাড়ি আছো?’

বৃষ্টি পড়ে এখানে বারোমাস

এখানে মেঘ গাভীর মতো চরে

পরান্মুখ সবুজ নালিঘাস

দুয়ার চেপে ধরে—

‘অবনী, বাড়ি আছো?’

আধেকলীন—হৃদয়ে দূরগামী

ব্যথার মাঝে ঘুমিয়ে পড়ি আমি

সহসা শুনি রাতের কড়ানাড়া

‘অবনী, বাড়ি আছো?’

Are you home, Abani

The neighbourhood is asleep behind closed doors,

I hear the night’s knock on my door

“Abani, are you home?”

It rains all year round here

Clouds graze the skies like cows

Young green grass, keen,

Clasps the door —

“Abani, are you home?”

Half-dissolved, I slide into sleep

Amid the heart’s distant pain.

Suddenly, the night rattles my door,

“Abani, are you home?”

The original article titled “Ke Abani, kaar baaRi, kenoi baa achhe” (কে অবনী, কার বাড়ি, কেনই বা আছে) was first published in the magazine Poetry Review, Shakti Chattopadhyay Special Issue, November 25 2000. It has been later collected in Amar Bondhu Shakti (আমার বন্ধু শক্তি) by Samir Sengupta; published by Parampara, Kolkata in 2011.