First published in DNA

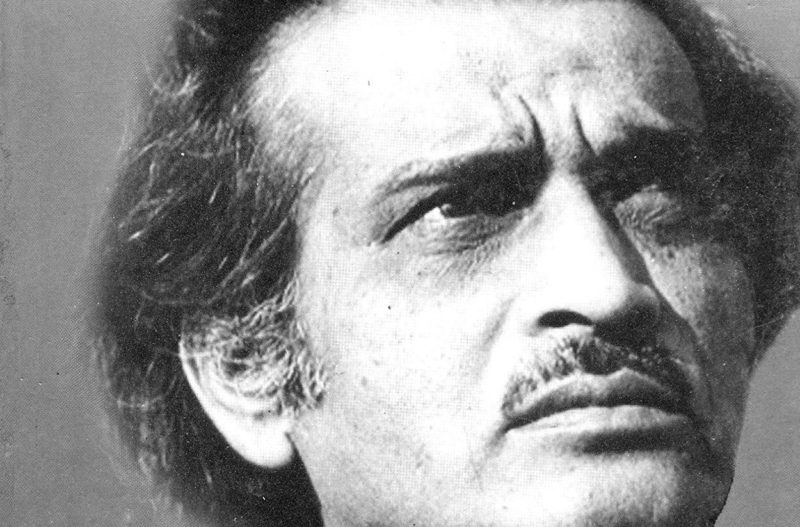

By delving into the poetic oeuvres of Namdeo Dhasal and Amiri Baraka, two towering voices representing the marginal, one comes closer, in a somewhat unsettling way to the lives of the oppressed and the outrage such an existence can cause. With both poets, the blaze of words often leaps off the printed page to singe the reader — with guilt, violence and even catharsis. The similarity doesn’t end there.

Dhasal, the Marathi “underground” poet and Baraka, the Black Arts revolutionary poet, playwright, music historian, find much of their literary ammunition in the life and surroundings in which they are rooted. Poetry for them isn’t about romanticising in tranquillity. Nor is it separate from activism.

“…we want ‘poems that kill’./ Assassin poems, Poems that shoot/ Guns.” — Black Art, Amiri Baraka

Dhasal echoes this idea of poetry being a weapon of protest, without caring much for labels such as political or social poetry. . “…As long as there remain contradictions and conflicts between individual and collective life that affect my feelings, my poetry will be about them,” he says. This rootedness, a sense of where they come from is the constant even as the two men evolve in or deviate from their affiliation to different ideologies over the course of their lives.

In Pur-Kanersar, the village where Dhasal was born and spent part of his childhood, even water — elementally unrestricted — had been divided. The up-river portion of a small river that ran through the village was the exclusive reserve of the privileged castes while the village’s oppressed untouchables were allowed to draw water from only the down-river part.

“Upstream, the water is all for you to take/ Downstream, the water is for us to get/ Bravo! Bravo! How even water is taught the caste system.” — Water, Namdeo Dhasal.

Though separated in age by more than a decade and born in different countries, both Dhasal and Baraka represent larger traditions within their own milieus — traditions of oppressed and dehumanized peoples. Their dissent is not theirs alone — it is a pastiche, if a dissonant one — of the anguished cries, pent up for centuries, within millions belonging to their tribes.

This irrepressible need to break the silence and galvanize the voices of the silenced led these two iconic men to establish socio-political platforms. Disillusioned with the existing framework of racial discourse in America, Baraka became a founding member of the Black Arts Movement, which would lead to many an African-American artist gaining traction in that country’s literary thoroughfare.

“We are beautiful people/ With African imaginations/ full of masks and dances and swelling chants/ with African eyes, and noses, and arms/ tho we sprawl in gray chains in a place/ full of winters, when what we want is sun.” — Ka’Ba, Amiri Baraka

Dhasal’s watershed moment would arrive in 1972. That year Golpitha, his first collection of poems, broke new ground in Marathi poetry, by smashing linguistic and idiomatic barriers, written in, what Dilip Chitre, Dhasal’s long-time translator and friend calls, “an idiolect fashioned in the streets of the red light district of central Mumbai, and from the Mahar dialect…his (Dhasal’s) native tongue.” In the same year, Dhasal also founded Dalit Panther, an organization on the lines of America’s Black Panther, to politically unite Dalits.

The poems in Golpitha sear with rage against suppression on the one hand and the helplessness of those on the receiving end of such systemic oppression on the other. In a tone mnemonic of Baraka’s outburst in Black Art, Dhasal unleashes his furore on the page in Man, You Should Explode.

“F**k the mothers of moneylenders and the stinking rich/ Cut the throat of your own kith and kin by conning them; poison them, jinx them”

Using ostensibly brazen and often crude language, the long poem lambasts symbols of effete aesthetics cherished by the privileged castes and calls for a complete breakdown of existing civil and social norms and structures. All this upheaval isn’t without hope though — in the form of the resulting implosion.

“After this all those who survive should stop robbing anyone or making others their slaves/ After this they should stop calling one another names — white or black, brahmin, kshatriya, vaishya or shudra;… One should regard the sky as one’s grandpa, the earth as one’s grandma/ And coddled by them everybody should bask in mutual love.” — Man, You Should Explode, Namdeo Dhasal

Both Dhasal and Baraka are credited with developing new lexicons geared towards and representing their particular audiences. They both played a seminal role in redrafting the manifesto of their respective agendas — equality for Dalits and that for Blacks.

“If you ever find/ yourself, some where/ lost and surrounded/ by enemies/ who won’t let you/ speak in your own language/ who destroy your statues/ & instruments, who ban/ your omm bomm ba boom/ then you are in trouble/ deep trouble/ they ban your/ own boom ba boom/ you in deep deep/ trouble/ humph!” — Wise I, Amiri Baraka.

Indeed Baraka and Dhasal have both been pioneers in carving out a space for literature from the margins. However, they too had other influential figures to guide them in their quest. If for Baraka it was Malcolm X, whose assassination triggered the Black Arts Movement, for Dhasal, the overarching impact of Dr BR. Ambedkar, himself a Dalit and a champion of equality, is a constant. Time and again, Dhasal invokes Ambedkar in his poems, lamenting how much of what the visionary statesman dreamed still remains unfulfilled.

“You are that Sun, our only charioteer,/ Who descends into us from a vision of sovereign victory, / And accompanies us in fields, in crowds, in processions, and in struggles;/ And saves us from being exploited.” — Ode to Dr Ambedkar, Namdeo Dhasal

Rooted yet restless, armed with deep convictions yet manifesting puzzling contradictions, these two poets of protest have come under criticism for their debatable ideological stances from time to time. Baraka’s pronounced homophobic and anti-Zionist utterances have unsettled readers and critics as much as Dhasal’s support for Indira Gandhi, the Shiv Sena and even the RSS shocked his friends and admirers.

For all the controversy both these poets courted, the depth of their words — smouldering embers in verse — makes them not only significant but indispensable chroniclers of the history, trauma and defiance of the repressed. Even if that entails disturbing refined sensibilities.

“I am a venereal sore in the private parts of language.” — Cruelty, Namdeo Dhasal

“My color/ is not theirs. Lighter, white man/ talk. They shy away. My own/ dead souls, my, so called/ people. Africa/ is a foreign place. You are/ as any other sad man here/ american.” — Notes For a Speech, Amiri Baraka