First published in hākārā

As she spread it over Dharala’s breast, heaving and restless, each fold of the meshed fibre courted a brisk movement of Fatima’s limbs. For maximum catch. The cast net yielded more readily to her commands now. The river had become just as adept at catching her secrets. There was only so much you could hide over a three-year relationship.

Taming the net hadn’t been easy for Fatima. In those initial months, after the truck crushed Masud’s hand, her rickety frame could barely grab the massive net without skidding into the river’s swampy edge. For almost a year, between hospital visits and the battle to ensure Masud didn’t sleep on an empty stomach, Fatima had experienced little luck honing her fishing skills. With a bed-ridden Masud, the couple lived almost entirely on the greens that Fatima foraged during her failed fishing expeditions. Rafiq brought them geri-gugli and chuno maachh every now and then, for which he refused even a hint of payment. Periwinkles and small fish weren’t items he would sell to Masud, a neighbour and his fishing partner, until only recently. Masud’s unforeseen disability saw Rafiq and Tarannum turn into the parents Masud and Fatima had lost a few years ago.

Fatima dragged the net out of the river’s bosom. With her feet submerged in Dharala’s anchoring grip, she shuddered as the memory of the days after Masud’s accident came rushing back to her. Days that had felt chilly even in the burning joishthho heat. She had barely recovered from the loss of the child in her womb when the truck hit Masud. Her unborn child still jolted her out of sleep at night. Clumps of sweat embossed her face every time she struggled to imagine what the baby’s face would look like if it were born. She would find herself gagging and in need of a sip of water to be able to breathe again.

She would be a day person, Fatima had decided over these three years. Nights were never kind to her. Night, the skinny ghost, an owl’s hoot. It echoed with the sound of whispering laughter and then of footsteps, making the darkness even more viscous. It carried the trapping scent of hasnuhana floating from somewhere nearby. And of the memory of hands rubbing her shoulder and grabbing at her breasts before she could make sense of it all … Nights were irreconcilable for Fatima, like the slick of fish oil that refused to be washed off. She never said a word to him, but Masud smelled the fear on her skin. He forbade her from going out after sunset.

For months that added up to almost a year, Fatima could barely replace a fraction of Masud’s income – by planting paddy on other people’s farms during the sowing season and then winnowing it for well-off families, selling a handful of eggs from the two chickens she reared, and cleaning the houses of neighbours for weddings and Eid celebrations. That and the generosity of Rafiq and Tarannum helped them survive, even if it meant Fatima had to practically give up rice herself and eat jowar flour boiled in water and mixed with some greens instead. The scent of steaming rice, which she now cooked exclusively for Masud, made her crave it more than ever before. She trained herself to restrain this instinct by rolling the end of her sari into a ball and covering her nose the moment the rice grains began bubbling in the water.

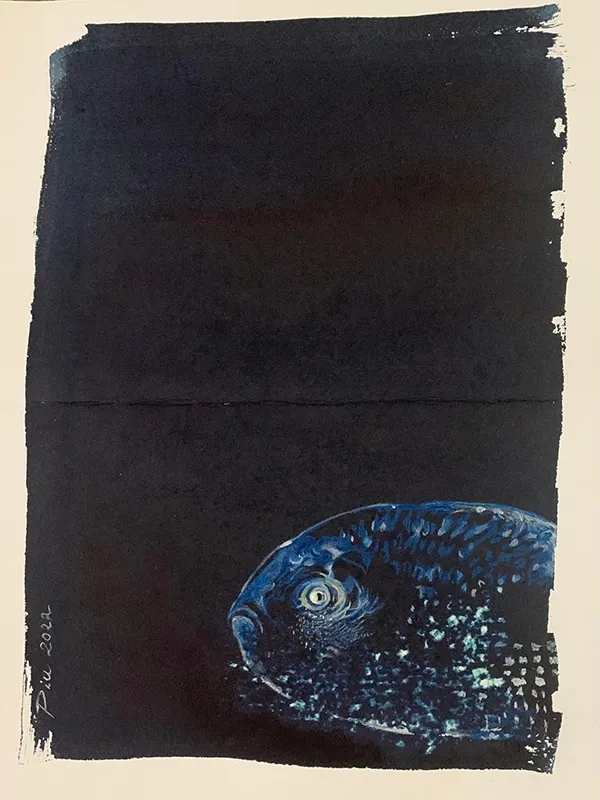

On some days, before returning home from the odd jobs she’d taken up, Fatima sauntered off, tired and heavy, to Rafiq’s house for a break. And for a mission. Tarannum was teaching her how to use a cast net. They worked with a net that Rafiq had discarded after it wore out in more than a few places. Tarannum showed Fatima how the best results were achieved by knowing when to let go and when to rein it in. You had to allow the rope to slip through your hand so the net could smoothly hit the bottom, and then as soon as it did, you needed to get a good grip on the rope and pull it right back up, lest the catch escaped. Seeing Fatima’s interest, Tarannum mended the net bit by bit and the two women began fishing, at first in the pond adjoining their house and then in Dharala. That’s when Fatima began sharing her secrets with the river. On most days, they got a decent enough catch of assorted fish. The women would split the haul, but not before releasing the small fish they caught into the river.

It seemed funny to Fatima how she and Tarannum had become fishing partners, the same way Masud and Rafiq had once been. The previous Eid, Rafiq had combined three decades’ worth of his savings with a particularly large remittance from his older son, a construction worker in Dubai, to buy a second-hand boat. For Masud, who was many river lengths away from getting his own boat, Rafiq’s new acquisition came as a blessing. He no longer had to pay rent for using another man’s boat, and Fatima and he began enjoying more fish-and-rice days.

Masud planned to combine a few months’ savings to put up a new roof. The constant leakage during the monsoons made Fatima ill every year. Now that she was expecting, he couldn’t let his baby arrive under a dripping roof.

Good fortune has a special allergy for poor people, Fatima would infer soon. The truck got Masud’s right – his dominant – hand and the money saved for the roof went towards his treatment. Then, Fatima lost the child.

‘Who gave you the fish?’ Fatima didn’t miss the hiss in Masud’s voice.

‘Tarannum apu. They’re having guests today, she had some extra,’ Fatima said, hastening to change. A second more and Masud would definitely spot the streak of mud lining the base of her sari. He would spot the river on her.

‘Hmm,’ Masud said and turned over in bed. Lately, even the smallest of pricks bristled him.