Sabyasachi Nag, Poetry Editor for The Artisanal Writer, a Canadian journal and literary arts collective exploring, inquiring and celebrating the craft and practice of writing, interviewed me. We discussed by debut poetry collection, NOSTALGIC FOR A PLACE NEVER SEEN (Copper Coin Publishing) and other aspects of my poetic journey.

Sabyasachi Nag (SN): Congratulations on your first poetry title? How did you arrive at the collection, did you conceive of it first and went about constructing the poems or did the poems coalesce at some point into the collection? How did you settle on the title? Could you tell us a bit more about the voice of the narrator? Is it intended as a singular narrator or many: one consistent voice or polyphony?

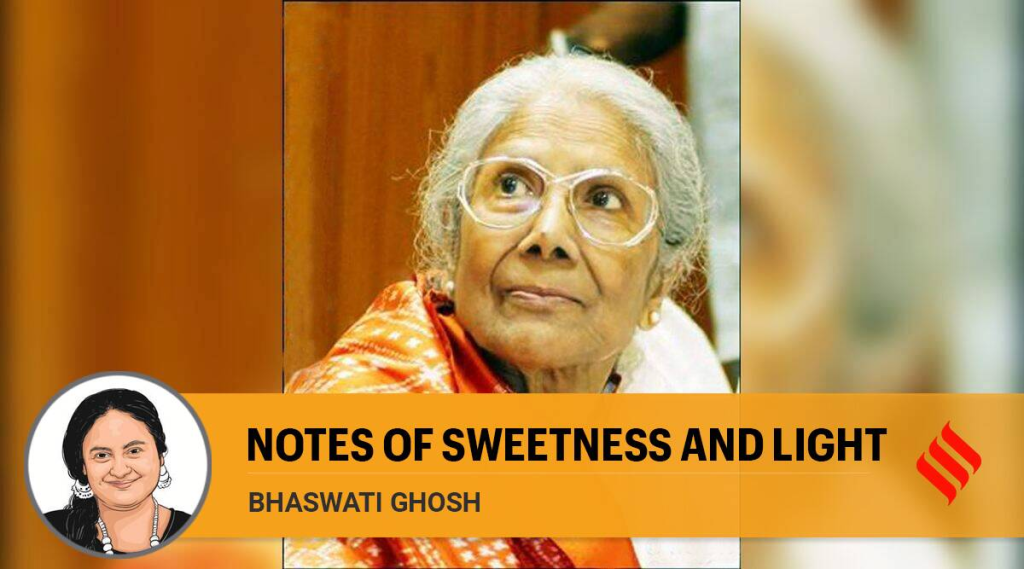

Bhaswati Ghosh (BG): The poems in Nostalgic for a Place Never Seen came about in a spontaneously serendipitous way. Until a few years ago, I was primarily a prose writer — dabbling mostly in creative non-fiction and the occasional short story. In August 2020, my debut novel, Victory Colony, 1950 was published.

In the spring of 2021, a friend who hosts a poetry-writing collective every April for the National Poetry Writing Month, invited me to join. This was at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic — we were housebound — and true to the cliches associated with poetry and solitude, the moment lent itself well to self-reflection. I enjoyed writing poetry in a collective — we read and shared feedback on each other’s works. This not only provided me with creative stimulus, it also brought camaraderie and connection at a time when we were dealing with isolation, anxiety and tragedy on an epic scale.

This exercise of writing a poem daily for a month for three years gave me enough poems to think of a collection while also allowing me to hone my craft and learn from fellow poets. Eventually I could see certain patterns and themes in the poems. The book’s title derives from one of the poems in the collection bearing the same title.

I would hesitate to pin a singular voice to the poems in this collection. More than a narrator expressing them, I feel poems breathe with their own life force and the poet is more like a vehicle bringing them to the surface.

SN: Although the book is sectioned in seven parts: dwellings; faces; scents, tastes and textures; seasons; elements; music; words and movements – there is a thematic circularity as it starts with displacement and ends in displacement. Is that intentional? The title alludes to a place never seen – so obviously this is a book about places – but is that place a reconstruction or recollection – is it a real place or a place from mythology?

BG: It’s less intentional than it appears to be. Many of the poems in the collection were written using prompts from various sources. When bringing them together, it seemed like a good idea to segment the poems thematically to help readers move through the collection with ease. Think of these as signs along a hiking trail in a forest. As one reader noted in her review of the book, “Thankfully the book is divided into sections, giving context and guidance as the poet shares the universe of memories and impressions that her senses have gathered and her mind synthesized.”

Many of the poems in the book do deal with the idea of location — both temporal and figurative. This made the idea of being nostalgic for a place that’s not merely physical but encompasses more — histories, memories, dreams, longings — pertinent.

SN: The book is wonderfully peppered with non-English words (mainly Bengali, your mother tongue). Is it about getting the voice right? Could you talk a bit about your process guiding your syntactic choices in this collection? Are you guided by meaning, and is there a point where you stop translating words from the mother tongue? Or do you arrive at a poem with a certain sound construct that you then look for the language and settle on words that evoke that sound?

BG: When writing poetry, one works within certain frameworks — in terms of form and structure but also atmosphere and aesthetics. In doing so, I occasionally leaned on words from Bengali or Hindustani to evoke a particular sense of the local. I see these insertions as both geographical signposts and emotive sparks that flow into a poem. They carried a spirit all of their own and had to be left there.

It’s difficult to put a finger on what triggers such word choices — it could be the intonation or musical texture peculiar to a word or phrase, but it could also be a very specific and indelible memory associated with a word, its pre-history and the sensory response it generates — not only within the poet but also among those who might be familiar with that expression. As a reader, being part of a world that’s more interconnected than ever, these interventions make poetry even more exciting and attractive to me.

In his essay Bringing Foreign Language to the Poem, Eric Steinger writes, “As poets, I believe we should take advantage of our available resources. Doing so can make poems interesting, nuanced, authentic, and contribute to the poem’s/poet’s voice.” This resonates with how some of the music-themed poems in Nostalgic for…evolved, using terms from traditional North Indian classical music systems.

SN: Several poems revolve around central characters – the grandmother (there are almost 20 references), mother (approximately 25 references) and father (10 references)…how much of this collection is autobiographical?

BG: I think that of all genres, poetry is probably the most autobiographical, as if by default. Even when a poem itself is not derived from one’s life arc, it’s a distillation of the poet’s inquiry into the subject at hand. That said, a fair bit of Nostalgic for…is indeed autobiographical — it’s an exploration of places, relationships, displacement — the last of these is perhaps the most pronounced of all the themes in the collection, heightened even more by my experience as an immigrant in Canada, my home since for almost a decade and a half now. As I made this long-distance journey to North America from India following my marriage, I began to sense, for the first time, the loss my grandmother might have felt when she’d been uprooted from her home in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) at the time of India’s independence in 1947 when the country was divided into India and Pakistan. Her stories of displacement and the trauma that accompanies it were no longer abstract tales for me; they became real as I too began experiencing the twinges of separation from home (New Delhi in my case), my family and loved ones.

SN: The narrator alternates between participant, witness and celebrant – is this collection a spoken record and oral testimony a conversation with history or a response to a “place never seen” and hence a void?

BG: It’s all of these descriptors you refer to — I couldn’t have said it better. The poems were written at different points in time and in disparate geographical settings, which might explain the switch between the voices. Quite a few of them came to me during my travels to Latin America, a region that fascinates me endlessly. My visits to places such as Mexico City (Mexico), Havana (Cuba), Cartagena (Colombia) and Buenos Aires (Argentina) have uncannily filled me with a sense of homecoming, owing perhaps to, the tropical climate, general chaos, and a profusion of colour, music and bustle of these places.

Then there are poems (Native Dialect, Nostalgic for a Place Never Seen, Milking Green Blessings) that relate to my grandmother’s loss of her homeland to the tragic event of India’s Partition I mentioned earlier.

The poems on music are deeply personal reflections of my responses to particular ragas (a melodic framework for composition, consisting of a specific set of notes and associated with certain emotions, times of day, or seasons).

There are poems on sensory delights such as food or scents, textures and sounds. In all of these explorations, the underlying quest is that of finding home as an antidote to the various types of voids I might be experiencing or holding within.

SN: How do you think the work responds to the questions it raises in the context of the timeand place the work is situated in?

BG: A lot of the poems in the collection relate to physical spaces — dwellings, markets, villages, cities, hills — straddling between continents, atmospheres, cultures and time periods. They raise questions like whether dislocating from one place and relocating to another can really be permanent, except maybe in material terms. The collection contemplates on city life with all its paradoxical oddities and inexplicable pulls. It wrestles with the manner in which the demands of the here and now contend with the salve and cushion of memory. It unlatches the many dimensions of love and takes in with curiosity its lessons for the soul. It observes movement and seeks to inhabit the in-betweenness of journeys.

As an example, I wrote the poem, Sunset on the Malecón, after returning from a visit to Havana, Cuba in 2017. This was a city that held a lot of fascination for me, given the history of the Cuban Revolution, the tiny island’s resistance to US imperialism, its association with the former Soviet Union, the lionized personas of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. My stay in Havana in a post Soviet world, however, left me with more questions than answers. I found it a city in a time warp — unable to discard the past and yet desperate to step out of it in some ways.

Cars, once shiny, wrecks now, tire the streets.

On balconies, old men mask sighs with

cigarette smoke and loud confabs.

The morning that arrived many suns

ago ducked out like friends whose

empires collapsed overnight.

(From Sunset on the Malecón)

SN: Did you have an intended audience for the book?

BG: I didn’t have any audience in mind when writing the poems — that process is deeply personal for me. When I compiled the poems for preparing the manuscript, my hope was that the collection would find readers who can join the journeys — external and internal — the poems voyage along. There’s great satisfaction in hearing from reader friends about how a poem from the book took them back to their grandparents or reminded them of the various addresses they’ve lived at. So to answer the question, instead of aiming to reach particular audiences, I tried to put my faith in the book finding its own reader tribe.

SN: In pushing your work beyond your first title what were you most conscious of? What were/are you trying to achieve with this book in terms of your literary career?

BG: As I mentioned in a previous answer, this book happened in the most unexpected of ways — I had no expectations from it beyond that the poems within would touch those who read them. Writing can be a contradictory practice — at once allowing one to engage with and yet also disconnect from the busy, sad and often horrific world we find ourselves in. I’m ambivalent about the word “career” as a definition for any work, but literary work in particular. Like the travels through the places in Nostalgic for a Place Never Seen, writing, for me, is a road trip — staying open and curious through the drive and pausing at pit stops to rest and reflect.

SN: What was the most satisfying aspect about writing this book (other than perhaps thesatisfaction of finishing it)?

BG: The best part about writing the poems for this collection was the freedom to write them without knowing they could end up between the covers of a book. Participating in National Poetry Writing Month in April for the past four years has meant an entire month of writing poetry every day — and while that seemed daunting in the beginning, I was surprised to see how quickly that nervousness transmuted into joy and creative learning.

Writing with other poets was a bigger treat as it exposed me to a diversity of voices and styles while allowing me to find my own. Another element that made writing poetry immensely satisfying was the thrill of the unknown. A poem often begins with a kernel and not as a fully fleshed-out edifice. It can be quite an adventure to see how it emerges bit by bit and the point at which it’s deemed complete. This mystical element makes poetry very dear to me — both the reading and writing of it.

SN: How would you like this book to be taught – as a historical document, socio-political document or as a document about a certain kind of taste in writing or particular aesthetic, genre, literary style or something else?

BG: I see Nostalgic for a Place Never Seen as a synthesis of all those elements — it has family stories that bounce off the history of the Indian sub-continent, the politics of forced migration intersecting with urban anxieties, and an immigrant’s uneasy existence in parallel universes.

In the collection, I’ve also attempted to cross linguistic barriers with the hope that the poems are fluid enough for readers to enjoy them while partaking of certain flavours that might be unfamiliar at first. What’s exciting about having a book out in the world is the many meanings it then reveals. If this collection is ever used for teaching, I’d like it to make all those meanings available and perhaps be in conversation with each other.