A new column about literary journeys I will be curating in Saaranga. This inaugural post starts with my own story.

At seven — an age when writing only means filling the school homework notebook with the dreary repetition of my handwriting — the joy of reading arrives at my door. It’s a hot morning of my summer vacations in New Delhi, and like on most such mornings, I’m preoccupied with some or the other holiday homework — tasks designed to keep children in line and make them more tolerable to their family members for two long and sultry months. A postman knocks on our gate holding that rare item — a parcel — that lights up our faces with barely- concealed smiles. As my grandmother emerges from the kitchen and opens the package with her turmeric-stained fingers, out come the precious contents — a book of Bengali chhawra or rhyming verses and illustrated Ramayana and Mahabharata for children in Bengali — books she had ordered for me through relatives in Calcutta. The fun of words rolling into limericks and nonsense verse as you uttered them, of reading stories you didn’t have to write an exam for, of letting your mind fill with imagination what the words in the books left out — these must have been the initiation for me on the road to being a literary pilgrim.

*

The year I move on to middle school, I decide to switch schools. I’m glad I do, because in grade six, I find the teacher who would influence me the most in my life. Abha Das, a petite woman who wears crisp cotton saris and glasses on her small but penetrating eyes, doesn’t merely give lectures on the stories in our English textbook. She makes each one of the stories, which she takes days to finish, a riveting experience — at once an education in the craft of storytelling and reading with empathy and understanding. As she gives a lecture on E. R. Braithwaite’s To Sir with Love, she asks us to look back and think of the times we felt belittled because of our identity. By doing this — throwing us headlong at our vulnerabilities — she dissolves the distance between the narrator and us. Relating to the characters we read about in fiction in such a visceral way would help make me be a better reader even before I show any promise of being a writer. One morning, I would find the teacher waiting at the end of our morning assembly line. She’s there to thank me for a birthday card I’d left on her desk in the staffroom with a poem titled To Ma’am with Love. Her teaching would turn my joy of reading into a deeper love for words. I would now notice their intonation, their music, and recognize their inherent power to breed both love and violence.

*

Even as Abha Ma’am enthralls us in school, at home, too, another petite woman — Amiya Sen, my grandma — remains a force I can’t ignore. She’s a grandmother like every other, doting and endlessly patient, yet she’s more. I see her go to work at an office when no other friend’s grandmother does. She stitches the best frock dresses for me every Durga Pua and knits me sweaters with the most exquisite patterns every winter. She reads — books, newspapers, magazines, my school textbooks, packets made from old newspapers — like there’s no tomorrow. And she writes. She writes after returning from work, she writes in between cooking meals, she writes after running errands, she writes late into the night after everyone has fallen asleep, she writes the first thing in the morning before anyone wakes up. She has no writing desk to fulfill this fetish; I only see her writing on the floor where she sprawls on her stomach to lie on a straw mat, her arms resting on a pillow. She would be my first example of what a full-time writer truly means — not someone who has no job and earns their living through writing, but someone who steals and grabs every millisecond of available time to write while carrying out the seven thousand and nine other responsibilities that eat into her writing time. At thirteen, I write my first short story in Bangla and show it to her with nervousness. With a warm hug of approval, she encourages me to write more. Two years later, before I’m able to grasp the full scope of her writing artistry, she leaves the world. And she leaves me clueless about fighting loneliness, about living with the scary beast of loneliness.

*

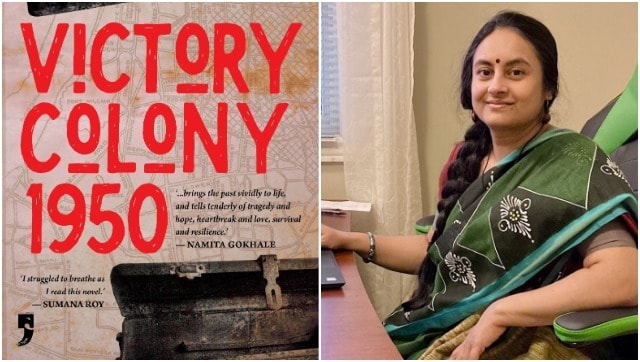

Three decades go by. I am far removed from the house I grew up in, the one that my writer grandmother built with her life’s savings and dreams. I now live with my husband in Canada where it’s cold for more than half a year. In the thirty years since my grandmother passed away and I passed out of school where Abha Ma’am taught me, I’ve carried more than luggage. I have lugged Grandma’s stories — literally and figuratively. I have with me a bunch of short stories she wrote longhand, to type out and prepare for possible publication. But I also have the stories she told me as I grew up — stories of her childhood back in undivided India, of her life as a young bride, of her coming to Delhi and learning the English alphabet from her children, of the heartbreaking and unrelenting tragedies she’d had to endure in her life, of the unceasing pain of being displaced from her desh, the native soil of East Bengal that she’d been estranged from with India’s division in 1947. Somewhere along the way, all of these make a story grow inside me, and I end up writing a novel. When Victory Colony, 1950, my first book of fiction is published, I feel happy, relieved and sad at once. Like every new author, I’m elated to finally see my story out there in the world. Yet somewhere inside, it hurts me to realize that the one person I would have liked to read it isn’t there.

A year after the book is published, I have a dream featuring my grandmother. She is lively and as engaged with current events as she always had been, and I feel anxious anticipating her reaction to my novel. When I wake up, a bittersweet sensation tugs at my throat. I feel relief and yet I also feel an ache.

Perhaps that is what our literary wanderings are about — arriving at life’s crossroads, with both pain and joy staring at us. It is my pleasure to welcome you all to Saaranga’s new column on these journeys with authors — I hope you’ll indulge us and enjoy taking in the songs, dramas and scenes that forge our writerly paths.